2.Changing Coastal Environments

2. Changing Coastal Environments

-

2.1.1 Coastal erosion: hydraulic action, corrosion, corrasion, attrition; transportation; deposition; longshore drift.

2.1.2 Types of waves: constructive and destructive and wave refraction. -

2.2.1 The characteristics and formation of landforms: headlands, bays, cliffs, wave-cut platforms, caves, arches, stacks, stumps, beaches, spits, bars, sand dunes.

2.2.2 The formation and characteristics of discordant and concordant coastlines.

-

2.3.1 The opportunities of living near the coast.

2.3.2 The hazards of living near the coast.

2.3.3 An evaluation of hard and soft engineering strategies and techniques used to manage coastal erosion and flooding; including sustainable.

2.3.4 The distribution and impacts of tropical storms: cyclones, hurricanes, and typhoons.

2.3.5 An evaluation of the strategies and techniques used to manage the impacts of tropical storms: preparation, planning, protection, prediction.

2.3.6 The global distribution, importance of, threats to, and strategies and techniques used to protect and manage coral reefs and mangroves; including sustainable.

2.3.7 One detailed specific example of a named country or coastal area to include:

• the causes and impacts of coastal erosion

• the strategies and techniques used to protect the coast from tropical storms and manage erosion; including sustainable.2.3.8 One detailed specific example of a named country or coastal area to include:

• why the coral reef is important

• threats to the coral reef

• the strategies and techniques used to protect and manage and the coral reef; including sustainable.

2.1 - Physical processes that shape the coast

Erosion

Erosion is the process where the sea wears away rocks and land along the coast.

Waves crash against the shoreline, gradually breaking down cliffs, beaches, and headlands.

This happens through several processes, including:

Hydraulic action – the force of waves trapping and compressing air in cracks.

Corrasion – waves hurl rocks and sand against the coast, like sandpaper.

Attrition – rocks and pebbles carried by waves smash into each other, becoming smaller and rounder.

Corrosion – some rocks (like limestone) are dissolved by acids in seawater.

Why it matters: Coastal erosion shapes landforms such as cliffs, caves, arches, stacks, and bays, and can also create hazards for people living near the coast.

Types of Erosion

Transportation

Transportation is the process by which the sea moves eroded material (sand, pebbles, mud) from one place to another along the coast. Waves and currents provide the energy needed.

There are four main types of transportation:

A. Solution

Some minerals (e.g. chalk, limestone) are dissolved in seawater.

They are invisible but still transported as part of the water.

B. Suspension

Fine, light material such as sand and silt is carried within the water.

It makes the water look cloudy or muddy.

C. Traction

Large boulders and rocks are rolled along the seabed by strong waves.

Happens in high-energy conditions (e.g. storm waves).

D. Saltation

Smaller pebbles and stones are bounced or hopped along the seabed.

They are lifted by the water, travel a short distance, and then land again.

Deposition

Deposition is the process where the sea drops or lays down material (sand, shingle, silt, pebbles) that it has been transporting.

When Does Deposition Happen?

Deposition occurs when the sea loses energy and can no longer carry its load. This often happens when:

Waves enter a sheltered area such as a bay.

The sea is shallow, slowing wave energy.

There is little or no wind, so waves are weaker.

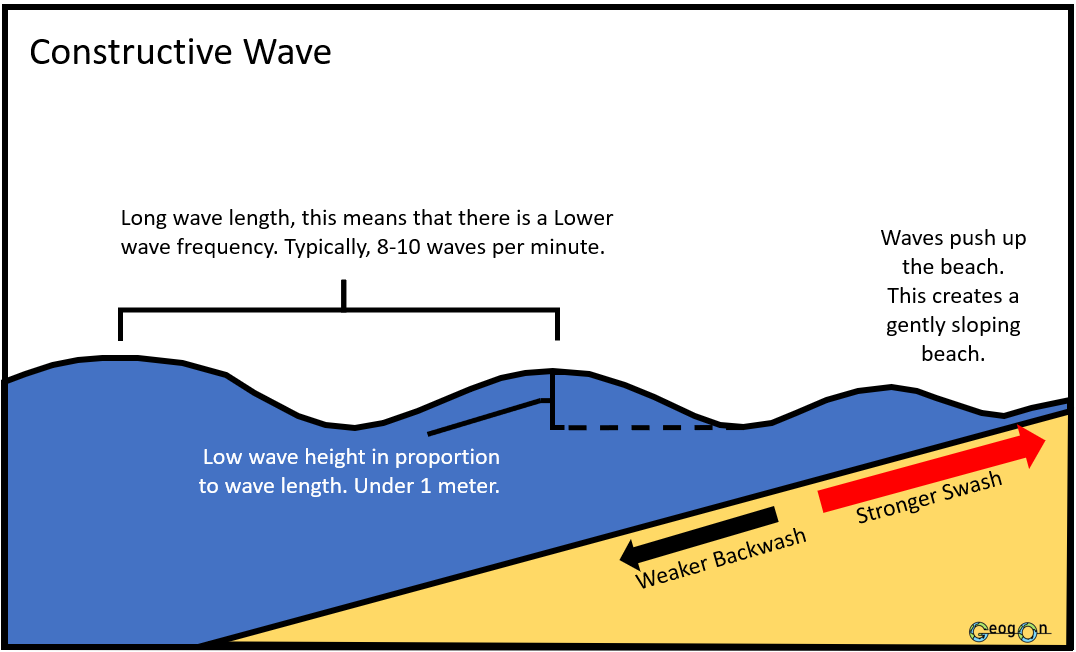

The swash is stronger than the backwash (constructive waves).

Exam Tip:

If asked “why does deposition take place?” always link to loss of energy in the waves. If asked about landforms, give a named example (e.g. Spurn Head spit, Holderness Coast, UK).

Exam Tip:

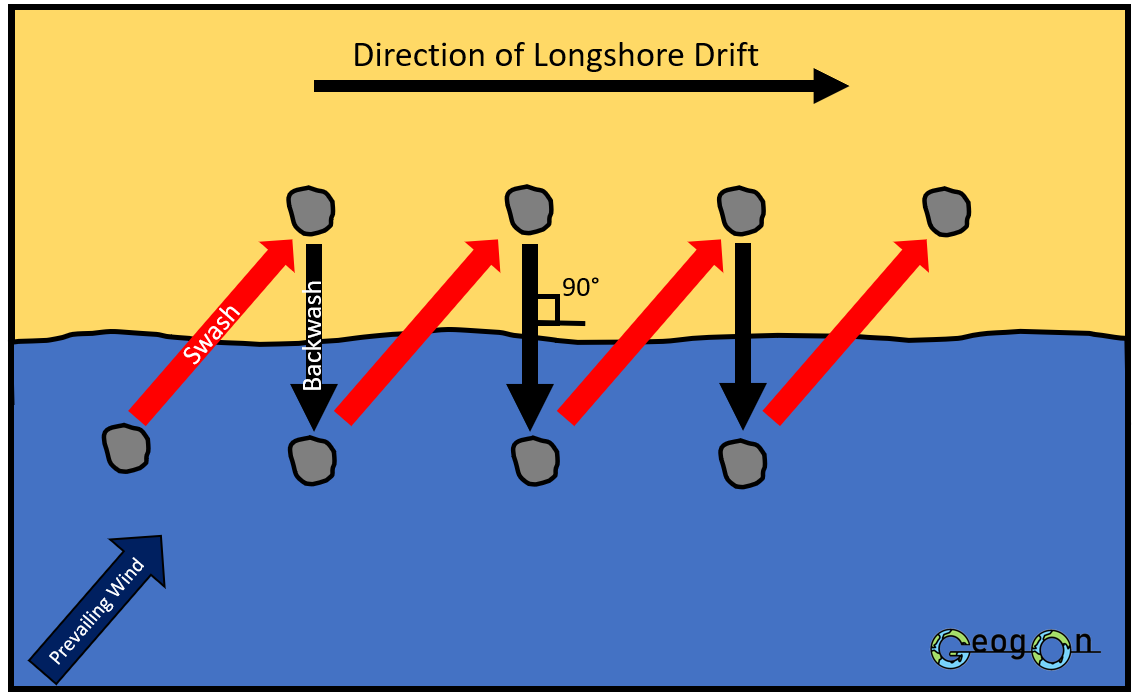

In a 4-mark question, always mention the swash, backwash, and angle of waves. Use the phrase “zig-zag movement” to show understanding.

Longshore Drift (LSD)

Longshore drift is the process that moves material (sand, shingle, pebbles) along a coastline in a zig-zag pattern. It happens because of the direction that waves approach the shore.

How it Works

Waves approach the coast at an angle (often driven by prevailing wind).

The swash (water moving up the beach) carries material up the shore at the same angle.

The backwash (water moving back down) is pulled by gravity and moves straight down the slope of the beach, at 90° to the coastline.

Repeated swash and backwash cause material to move step by step along the coast.

Why is it Important?

Longshore drift is the main process transporting sediment along coasts.

It plays a key role in forming depositional features such as:

Spits

Bars

Tombolos

It can also lead to erosion in some areas when sediment is removed.

Waves

What are Waves?

Waves are created by the wind blowing across the surface of the sea.

The strength, duration, and distance of the wind (called the fetch) control the size and power of waves. In the diagram A would produce the largest and strongest waves. This is because it has the largest fetch.

Parts of a Wave

Crest – the top of the wave.

Trough – the lowest point between two waves.

Swash – the forward rush of water up the beach after a wave breaks.

Backwash – the water running back down the beach under gravity.

Why Do Waves Break?

As waves move from deep water into shallow water, the base of the wave slows down due to friction with the seabed. The top of the wave continues moving faster than the bottom. This causes the crest to become steeper until it collapses forward, breaking onto the shore.

Types of waves

Constructive Waves

Low, gentle, and less frequent.

Strong swash, weak backwash → material is deposited.

Create wide, gently sloping beaches made of sand or shingle.

Destructive Waves

High, steep, and frequent.

Strong backwash, weak swash → material is eroded and dragged away.

Create narrow, steep beaches with coarse material.

Wave Refraction

What is Wave Refraction?

Wave refraction is the process by which waves bend and change direction as they approach the coastline. It happens because different parts of the wave reach shallow water at different times, causing the wave to slow down unevenly.

How it Works

In deep water, waves move at the same speed in straight crests.

As waves approach an irregular coastline, one end of the wave reaches shallow water first (e.g. around a headland).

Friction with the seabed slows this part of the wave, while the rest in deeper water continues faster.

The wave bends towards the headland, concentrating energy there.

In bays, waves spread out, and energy is reduced, leading to deposition.

Exam Tip:

Use phrases like “energy concentrated on headlands” and “energy dispersed in bays”.

Often tested in diagram + explanation style questions (3–4 marks).

2.2 - The Main landforms associated with these processes

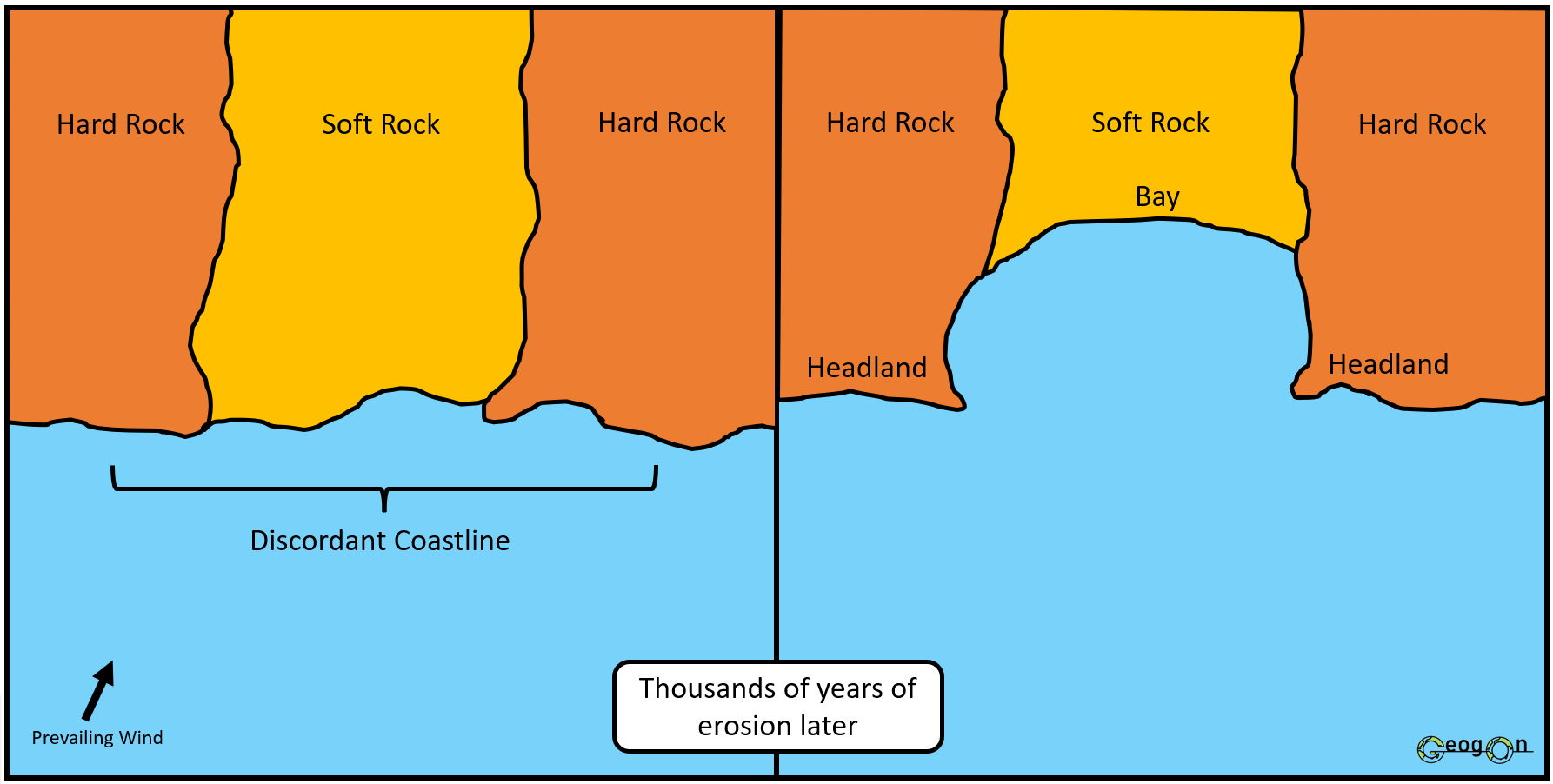

Discordant Coastlines

Coastlines where the bands of hard and soft rock run at right angles to the shoreline.

Rock types: Hard rocks (e.g. chalk, limestone) alternate with soft rocks (e.g. clay, sands).

Features formed:

Softer rock erodes faster (by hydraulic action and corrasion) forming bays.

Harder rock is more resistant and sticks out into the sea, forming headlands.

Waves refract around headlands → energy concentrated on them (erosion), energy dissipated in bays (deposition).

Classic features: headlands, bays, cliffs, wave-cut platforms.

Concordant Coastlines

Coastlines where the bands of rock run parallel to the shoreline.

Rock types: Usually a continuous band of hard rock (e.g. limestone, chalk) and soft rock (e.g. clay, sands) running parallel behind protected from the shore.

Features formed:

The hard rock acts as a barrier, protecting the softer rock behind.

The coastline remains fairly straight and uniform.

However, if erosion breaks through the hard rock (e.g. along a fault or weakness), the sea can erode the softer rock behind → forming coves (e.g. Lulworth Cove, Dorset).

Headlands and Bays

What are they?

Headlands are areas of hard rock that stick out into the sea.

Bays are curved inlets where the softer rock has been eroded away.

How do they form?

A coastline has alternating bands of hard and soft rock.

Waves erode the softer rock faster (processes: hydraulic action, corrasion, corrosion).

This creates bays.

The harder rock is more resistant, so it erodes slowly and sticks out as headlands.

Wave refraction causes more energy to hit the headlands (further erosion) and less energy in the bays (deposition → sandy beaches often form).

Exam Tip:

In a 4–5 mark answer, always link rock type + erosion rate + landform. If asked to include a 2 stage diagram.

Wave-cut platforms

A wave-cut platform is a flat, rocky area found at the base of a retreating cliff. It is left behind after the cliff face has been eroded and collapsed many times. Wave-cut platforms are usually exposed at low tide and may have features like rock pools, seaweed, and sharp uneven rock. They are evidence of cliff retreat and show how the coastline has changed over time.

How do they form?

Waves attack the base of a cliff using hydraulic action, corrasion, and corrosion.

This erodes a wave-cut notch at the high tide level.

As the notch gets bigger, the cliff above becomes unstable.

Eventually, the cliff collapses under its own weight.

The cliff retreats inland, and the fallen rock is carried away by waves.

A flat, rocky area is left at the base, exposed at low tide – this is the wave-cut platform.

The process repeats, making the platform wider and the cliff retreat further.

Exam Tips:

Always use the sequence notch → collapse → retreat → platform in your answer.

In a short definition question, write something like:

“A wave-cut platform is a flat, rocky surface at the base of a cliff, formed by wave erosion and cliff collapse.”

Cave, Arch, Stack and Stump

What are they?

Crack or fault - an area of weakness that can be more easily eroded.

Cave – a hollow in a cliff formed when waves erode a weakness (crack or fault).

Arch – when a cave is eroded through a headland, forming a natural opening.

Site of collapse - This shows the area where an arch used to stand.

Stack – an isolated vertical column of rock left when an arch collapses.

Stump – the eroded remains of a stack, usually visible at low tide.

How do they form? (6 steps)

Waves attack a cliff with hydraulic action, corrasion, and corrosion. A crack or joint in the rock is gradually widened.

Continued erosion (Hydraulic action and corrasion) enlarges the crack into a cave.

Further erosion deepens the cave until it breaks through the headland, creating an arch.

The arch roof becomes unstable and eventually collapses.

The collapsing of the arch leaves behind a solitary column of rock called a stack.

The stack is further eroded at its base until it collapses, leaving a stump.

Exam Tips:

Always use the sequence crack → cave → arch → stack → stump.

Mention erosion processes (hydraulic action, corrasion, corrosion) for full marks.

Beaches

A beach is a landform made of sand, shingle, or pebbles found between the high tide and low tide marks. Beaches are depositional features, created when waves drop material they were transporting.

How do they form?

Constructive waves (strong swash, weak backwash) deposit sand and shingle.

Material often comes from cliff erosion, rivers, or longshore drift.

Deposition is greatest in sheltered bays where wave energy is low.

Types of beaches

Summer beaches → wide and sandy (constructive waves).

Winter beaches → narrow and steeper, with more shingle (destructive waves).

Spits

Exam Tip:

Always include the sequence of wind + longshore drift + headland + hook + estuary + salt marsh for full marks.

A labelled diagram showing longshore drift arrows, the spit, hooked end, and salt marsh is often expected in 4–7 mark questions.

A spit is a narrow ridge of sand or shingle that sticks out into the sea, joined to the land at one end.

Formed by longshore drift depositing material where the coastline changes direction (e.g. a river mouth).

Example: Spurn Head, UK.

What is a spit?

A spit is a long, narrow ridge of sand or shingle that sticks out into the sea, connected to the land at one end.

Formation of Spits

Prevailing wind and swash direction – waves approach the coast at an angle, driven by the prevailing wind.

Longshore drift – material is moved along the coast in a zig-zag pattern by swash and backwash.

Headland / change in coastline – when the coastline ends or changes direction (e.g. a river mouth), sediment is carried out to sea beyond the headland.

Hooked end – the tip of the spit may curve inland due to wave refraction or secondary winds.

Estuary limits growth – if a river estuary is present, its flow prevents the spit from fully crossing the water.

Salt marshes – sheltered water behind the spit becomes a low-energy zone where mud and silt build up, creating salt marshes.

A bar is when a spit grows across a bay, joining two headlands.

This can trap water behind it, forming a lagoon.

Example: Slapton Ley, Devon, UK.

A tombolo is when a spit connects the mainland to an island.

Example: Chesil Beach linking Portland to mainland Dorset, UK.

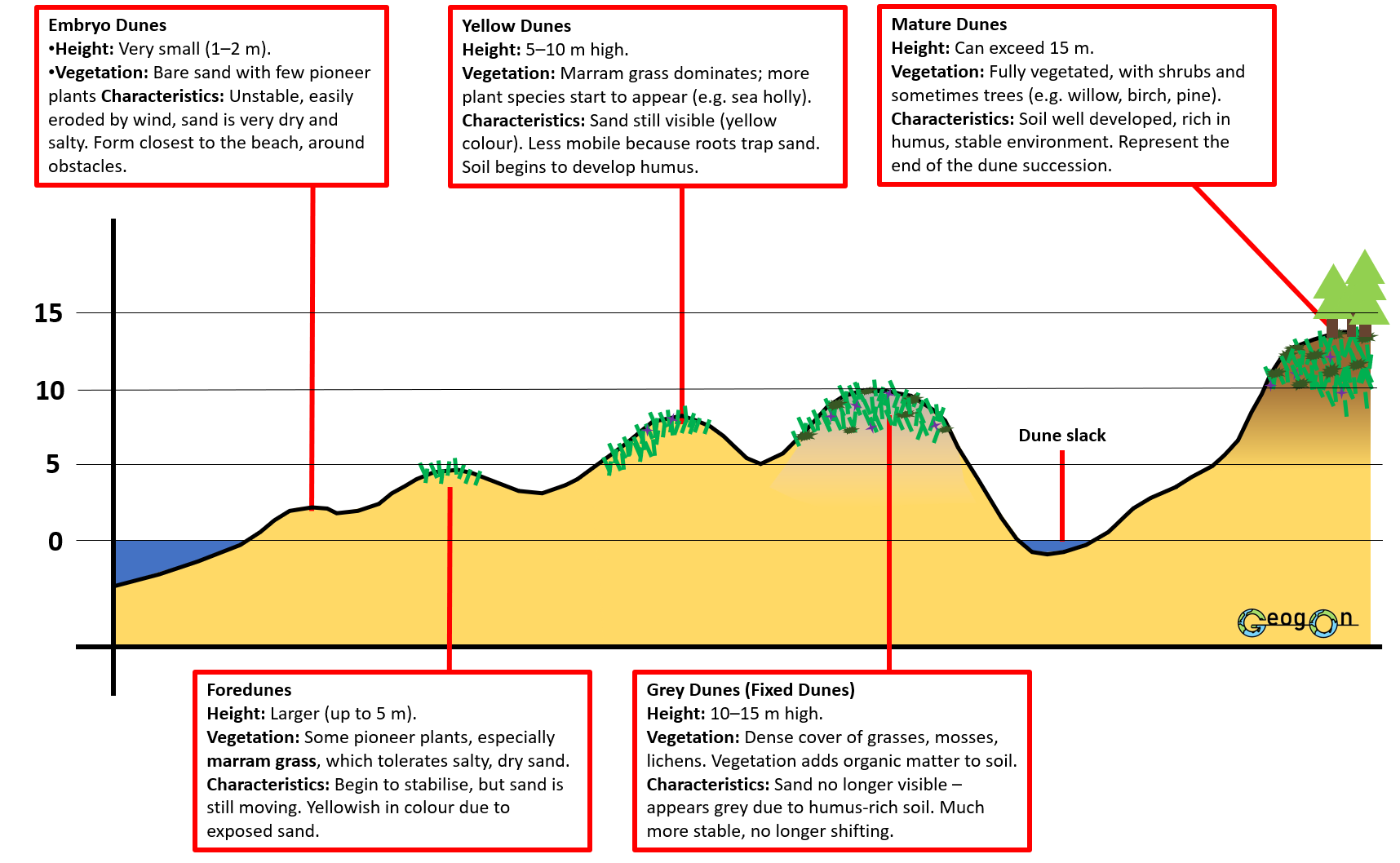

Sand Dunes

What are they?

Sand dunes are mounds or ridges of sand found at the back of beaches, shaped by the wind. They are depositional landforms, created when sand is blown inland.

How do they form?

Onshore winds blow dry sand from the beach inland.

Sand is trapped by an obstacle (e.g. driftwood, rocks, plants).

Small embryo dunes begin to form.

Plants such as marram grass grow on dunes, trapping more sand with their roots and stabilising the dune.

Over time, dunes get bigger and move further inland, forming a succession:

Embryo dunes – small, unstable, little vegetation.

Foredunes / Yellow dunes – higher, partly vegetated, sand still visible.

Grey dunes – larger, fully vegetated, soil develops (grey colour).

Mature dunes – stable, often with shrubs and trees.

Exam Tip:

In an exam, always link dunes to wind + sand movement + vegetation stabilisation.

2.3 - Coasts present opportunities and hazards for people

Opportunities of Living Near the Coast

Hazards of Living Near the Coast

Coastal Erosion

Why is coastal erosion a major hazard?

Coastal erosion is the wearing away of land and beaches by waves, currents, and tides. It is a major hazard because it destroys homes, farmland, businesses, and important infrastructure such as roads and ports. In some areas, whole communities are forced to relocate.

Example:

On the Holderness Coast (UK), soft cliffs made of boulder clay are eroding rapidly — up to 2 metres per year. Villages, farmland, and even roads have been lost to the sea, making it one of the fastest eroding coastlines in Europe.

Human management:

Although erosion is a natural process, humans can use different coastal management strategies to protect people and property from damage. These are divided into hard engineering and soft engineering approaches.

Shoreline Management Plans

A Shoreline Management Plan (SMP) is a strategy used to decide how to manage different stretches of coastline. Instead of each town making decisions alone, SMPs look at the coast as a whole and plan for the long term (50–100 years).

Purpose:

To reduce risks from coastal erosion and flooding.

To balance environmental, social, and economic needs.

To make coastal management more sustainable.

Decision-Makers in SMPs

1.National Government Agencies

2.Local Authorities (Councils)

3.Stakeholders

Hold the Line

Shoreline Management Plans Compared to War Tactics

Hold the Line → Like defending a fortress wall: troops hold their ground and strengthen their defences to stop the enemy (the sea) from advancing.

Advance the Line

Advance the Line → Like pushing troops forward: the army moves into enemy territory, gaining land but at huge cost.

Managed Retreat

Managed Retreat → Like a tactical withdrawal: the army gives up less important land to regroup and strengthen elsewhere, reducing long-term losses.

Do nothing

Do nothing → Like abandoning a battlefield: commanders decide it’s not worth the fight, so the army retreats completely and lets the enemy take over.

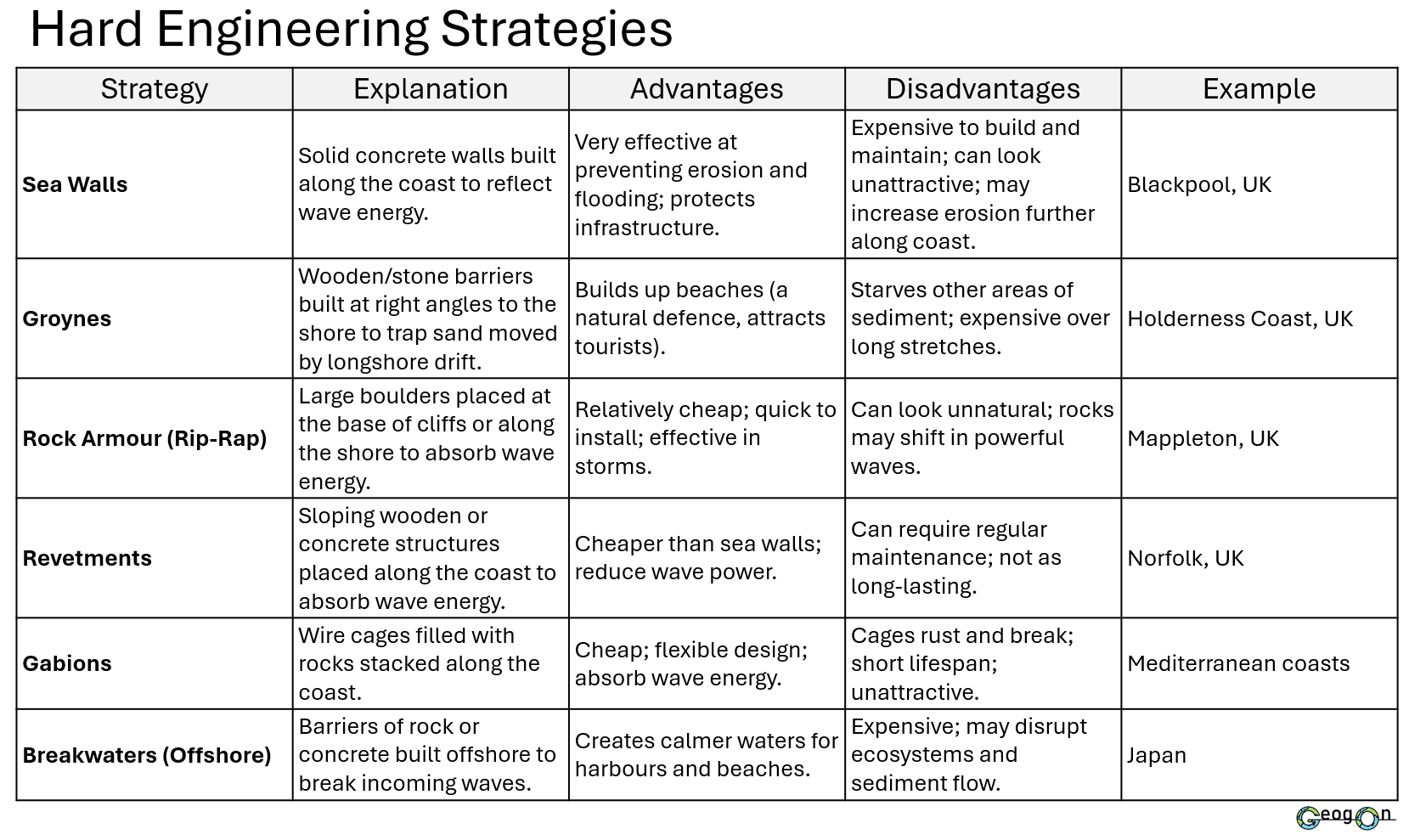

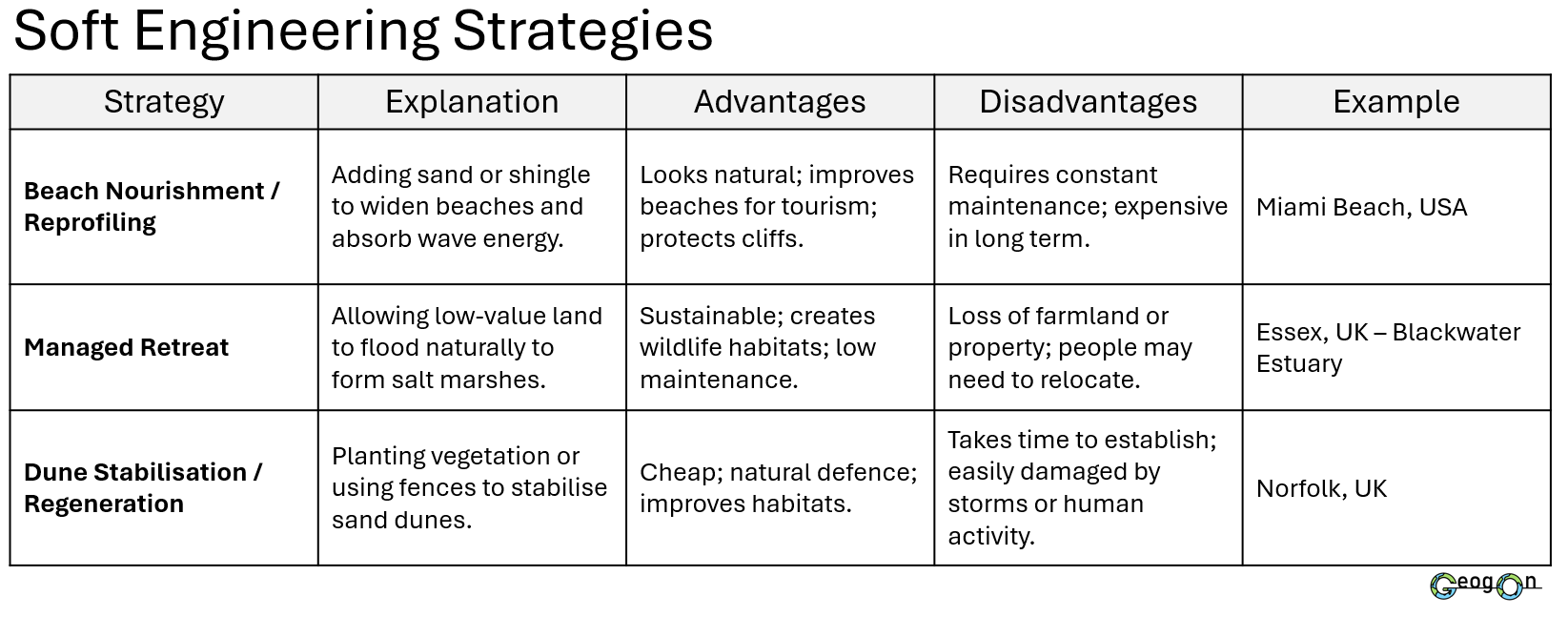

Hard Engineering and Soft Engineering

What is Hard Engineering?

Hard engineering involves building man-made structures to control the sea and reduce its power. These are usually expensive but provide strong protection.

Examples: sea walls, groynes, rip-rap, offshore breakwaters.

What is Soft Engineering?

Soft engineering works with natural processes to reduce the impact of the sea. It is often cheaper, more environmentally friendly, and more sustainable in the long term.

Examples: beach nourishment, dune regeneration, managed retreat, planting mangroves.

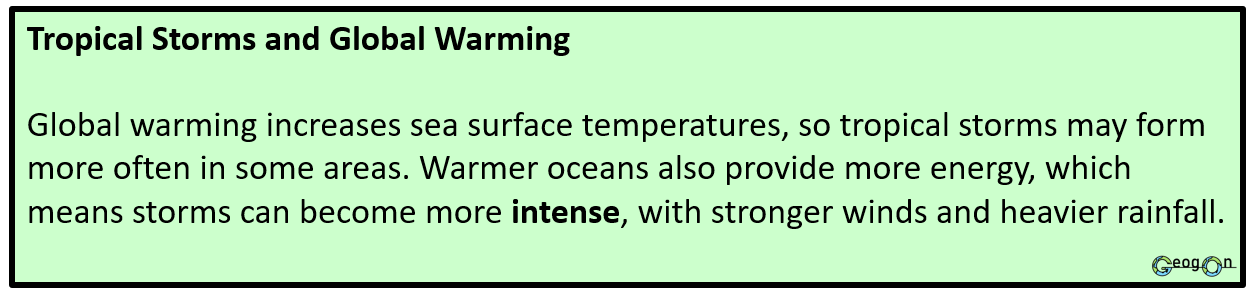

The Distribution and Impacts of Tropical Storms: Cyclones, Hurricanes, and Typhoons

Distribution of Tropical Storms

Tropical storms form over warm oceans close to the equator, where sea surface temperatures are above 27°C. They develop between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn but never exactly at the equator, as the Coriolis force is too weak there.

In the Atlantic and eastern Pacific Oceans, they are called Hurricanes.

In the western Pacific Ocean, they are called Typhoons.

In the Indian Ocean and around Australia, they are called Cyclones.

The arrows on the map show their typical paths (westward and then curving polewards), while the shaded red areas highlight where these storms most often occur.

Categorising Tropical Storms

The Impacts of Tropical Storms

Tropical storms can cause widespread social, economic, and environmental impacts. Strong winds destroy homes, power lines, and crops, while heavy rainfall and storm surges lead to flooding, landslides, and water contamination. Economically, transport networks and businesses are disrupted, and rebuilding costs can reach billions. The severity of these impacts often depends on a country’s level of economic development. In low-income countries (LICs), weaker infrastructure, limited forecasting systems, and slower emergency responses lead to higher death tolls and slower recovery. In contrast, high-income countries (HICs) like the USA can reduce impacts through early warning systems, evacuation plans, and stronger buildings, though financial losses are often higher due to the value of assets damaged.

What Are Storm Surges?

A storm surge is a sudden rise in sea level caused by strong winds and low air pressure during a tropical storm or hurricane. The intense winds push large volumes of seawater towards the coast, while low pressure allows the sea surface to rise even higher. When this surge combines with high tide, it can cause severe coastal flooding.

Storm surges often cause the most damage in tropical storms because they flood large coastal areas, destroy homes, contaminate freshwater supplies, and wash away beaches, roads, and farmland. In low-lying regions, even a few metres of water can inundate entire communities within minutes.

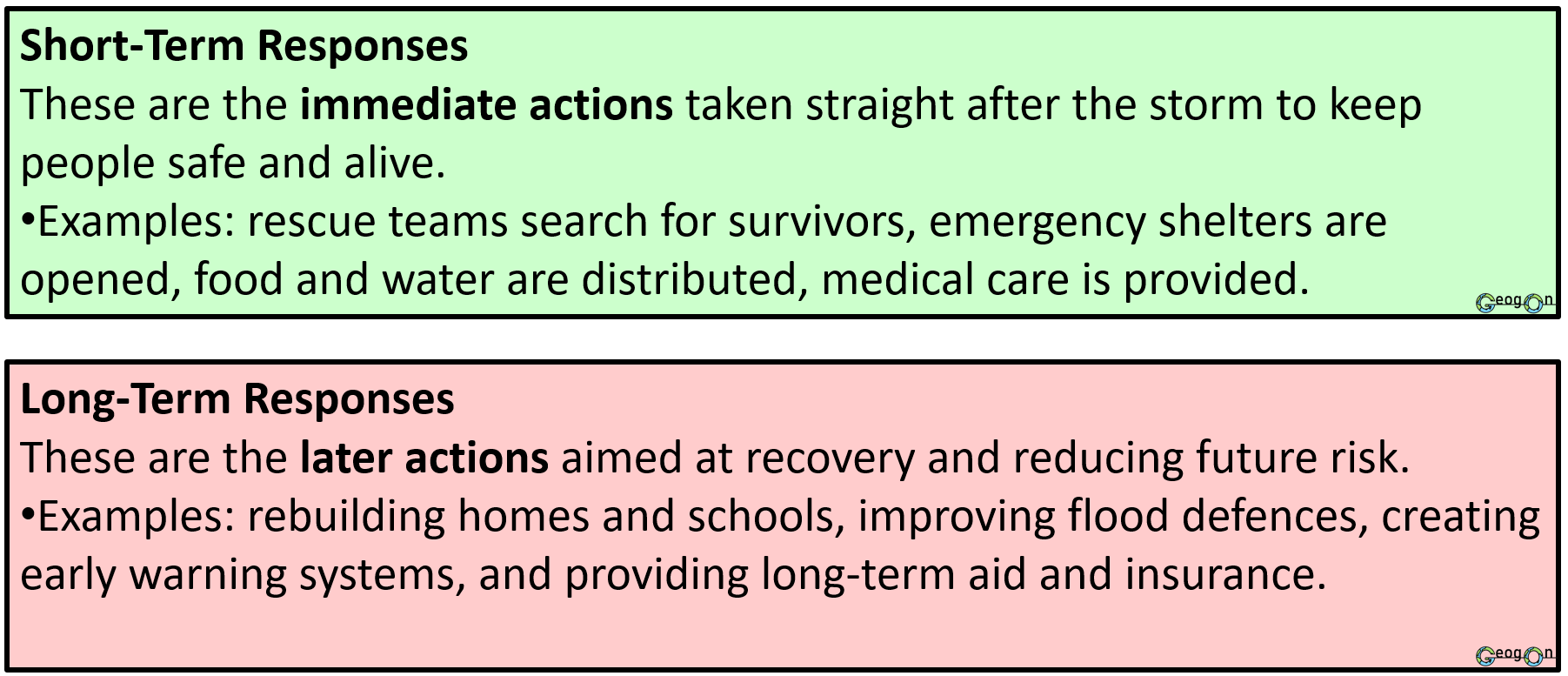

Managing Tropical Storms

Coral Reefs

What are they?

Coral - Tiny soft-bodied animal that typically lives within a stony skeleton grouped in large colonies

Coral reefs are warm, clear, shallow ocean habitats that are rich in life.

The reef's massive structure is formed from coral polyps, tiny animals that live in colonies; when coral polyps die, they leave behind a hard, stony, branching structure made of limestone.

As one animal dies, new ones grow on top, so coral reefs grow upwards and outwards.

Coral reefs are home to 25% of all marine fish species in the world while only covering less than 1% of the world's surface giving it a high level of biodiversity.

Where are they located?

There are coral reefs are between tropics and near the shore. Off the eastern coast of Africa, off the southern coast of India, in the Red Sea, and off the coasts of northeast and northwest Australia and on to Polynesia. There are also coral reefs off the coast of Florida, USA, to the Caribbean, and down to Brazil.

Threats to Coral Reefs

Climate Change: Rising sea temperatures cause coral bleaching, where corals lose their algae and turn white, often leading to death.

Ocean Acidification: Increased carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere dissolves into seawater, lowering pH and weakening coral skeletons made of calcium carbonate.

Tourism Pressure: Uncontrolled tourism, such as divers touching corals or anchors damaging reefs, physically breaks fragile coral colonies.

Management of Coral Reefs

Pollution: Run-off from farms, sewage, oil spills, and plastic waste pollute reef waters, blocking sunlight and reducing oxygen levels.

Overfishing and Destructive Fishing: Practices like blast fishing or using cyanide destroy coral structures and disrupt the food chain.

Coastal Development: Building resorts, ports, and roads near coasts leads to sedimentation that buries corals and reduces water quality.

The management of coral reefs involves reducing human impacts, restoring damaged ecosystems, and addressing global environmental change through local, national, and international action.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): Many countries have created MPAs to control fishing, restrict boat anchoring, and limit coastal development. This allows damaged coral ecosystems to recover naturally. For example, the Galápagos Marine Reserve limits tourist numbers and fishing activities, using entrance fees to fund conservation.

Global Climate Action: International agreements such as the Paris Agreement (2015) aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and slow global warming. This helps prevent coral bleaching, which is caused by rising sea temperatures.

Coral Restoration Projects: In places like the Maldives Resilient Reefs Project, scientists grow new coral fragments in nurseries and transplant them onto damaged reefs—a process known as coral propagation—to help rebuild healthy ecosystems.

Sustainable Fishing and Tourism: Destructive fishing methods like dynamite or trawling are banned in many regions. Eco-friendly tourism practices, such as using mooring buoys instead of anchors and avoiding touching corals, help protect fragile reefs.

Pollution Control: Reducing agricultural run-off, sewage discharge, and plastic waste improves water quality and prevents damage to coral ecosystems. Some regions have also banned harmful sunscreens that damage coral larvae.

Community Involvement and Education: Local communities, schools, and visitors are involved in reef monitoring, clean-ups, and education programmes. This builds awareness of reef importance and supports sustainable management practices.

Mangroves

What are they?

Mangroves are trees and shrubs that grow in tropical and subtropical coastal areas where saltwater and freshwater mix, such as river mouths, lagoons, and estuaries. They have special adaptations — like tangled roots called prop roots — that allow them to survive in salty, muddy, and oxygen-poor conditions.

Mangroves are important because they:

Protect coastlines from erosion, waves, and storm surges.

Provide habitats for fish, crabs, and birds.

Trap sediment and pollutants, improving water quality.

Store large amounts of carbon, helping to reduce the effects of climate change.

Where are they located?

Mangroves are found in tropical and subtropical coastal regions between roughly 30°N and 30°S of the Equator. They grow along sheltered coastlines, river mouths, and estuaries where saltwater and freshwater mix.

Large mangrove forests are found:

In Southeast Asia (e.g. Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand)

Along the east coast of Africa (e.g. Mozambique, Kenya)

Around the Caribbean and Central America (e.g. Cuba, Belize)

On the coasts of northern Australia

In the southern USA, especially Florida and the Everglades

They are most common on low-energy coastlines in warm regions where sea temperatures stay above 20°C all year round.

Threats and Management

Case study: Florida

Background Information

Florida is one of the most economically developed states in the USA. It has a large and diverse economy based on tourism, agriculture, trade, and services. Millions of visitors come each year for its theme parks, beaches, and warm climate, making tourism a major source of income. The state also produces citrus fruits, sugarcane, and vegetables, and its ports handle large volumes of imports and exports with Latin America. Geographically, Florida is a low-lying peninsula with over 2,000 km of coastline, a warm tropical to subtropical climate, and flat land that makes it both attractive for settlement and vulnerable to hurricanes and flooding.

Location

Florida is a state in the southeast of the USA, located in the continent of North America. It lies in the south-eastern region of the country. To the east it borders the Atlantic Ocean, and to the west it borders the Gulf of Mexico. It is close to the north of the Equator, lying between 24°N and 31°N. A key feature of Florida is its long, low-lying coastline with beaches, mangroves, and coral reefs that make it vulnerable to hurricanes and coastal erosion.

Causes of Erosion in Florida

Florida’s coastline is constantly changing due to a combination of natural and human factors.

Soft Rock Geology: Much of Florida’s coast is made from soft limestone and sandstone, which are easily worn away by waves.

Flat, Low-Lying Land: The land sits only a few metres above sea level, so even small rises in sea level or storm surges can flood and erode beaches.

Hurricanes and Storm Surges: Powerful tropical storms bring strong winds and waves that remove sand and damage coastal defences.

Longshore Drift: Wave action moves sand along the coast, causing some areas to lose material faster than it is replaced.

Sea-Level Rise: Linked to global warming, higher sea levels allow waves to reach further inland, accelerating erosion.

Human Activity: Coastal development, seawalls, and beach structures interfere with natural sediment movement, often worsening erosion in nearby areas.

Together, these processes make Florida one of the most erosion-prone states in the USA, especially along its popular tourist beaches.

Effects of Coastal Erosion in Florida

The FCMP

Coastal Management in Florida

The Four Ps: Managing Tropical Storms in Florida

Florida is one of the most hurricane-prone regions in the world, affected by storms such as Hurricane Andrew (1992), Hurricane Irma (2017), and Hurricane Ian (2022). The state’s management follows the Four Ps — Preparation, Prediction, Protection, and Planning — coordinated mainly by the Florida Division of Emergency Management (FDEM).

Preparation

Public awareness and drills: Before each hurricane season (June–November), the FDEM launches campaigns such as “Get a Plan!” encouraging households to prepare emergency kits, store food and water, and plan evacuation routes.

Evacuation and emergency shelters: There are over 3,000 designated hurricane shelters across the state, and counties issue evacuation orders when storm surge warnings are given.

Community response: Local authorities and volunteers conduct practice drills, particularly in coastal cities like Tampa and Miami.

Evaluation: Preparation saves lives but relies on people following guidance and being able to afford to evacuate. Rural and low-income communities often face the greatest challenges.

Protection

Hard engineering: Seawalls and levees in Miami, Tampa, and Jacksonville protect infrastructure from storm surges. The Miami Beach “Rising Above” project invests US$500 million in upgraded seawalls and pumping stations.

Natural protection: Mangrove forests in southern Florida act as natural buffers. During Hurricane Irma (2017), mangroves reduced flood damage by an estimated US$1.5 billion and protected over 625,000 people.

Infrastructure upgrades: Power lines are being buried underground to prevent outages, and flood-resistant designs are now used for hospitals and emergency centres.

Evaluation: Protection methods are effective but extremely costly and often limited to wealthier urban areas.

Prediction

Advanced forecasting: The National Hurricane Center (NHC) in Miami uses satellites, radar, and aircraft reconnaissance (“Hurricane Hunters”) to monitor tropical storms across the Atlantic.

Warning systems: Real-time alerts are sent through TV, radio, and mobile networks using the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS).

Lead time: Florida typically receives 2–5 days’ notice before landfall, allowing for evacuation and preparation.

Evaluation: Prediction accuracy has greatly improved, but storm paths can still shift unexpectedly, leading to costly false evacuations.

Planning

Building codes: After Hurricane Andrew (1992) caused over US$25 billion in damage, Florida introduced strict building codes (2002) requiring hurricane-resistant roofs and impact-proof windows.

Zoning and land use: The Coastal Construction Control Line (CCCL) prevents new buildings too close to vulnerable beaches.

Climate adaptation: Long-term plans under the Florida Coastal Management Program include living shorelines, mangrove restoration, and sustainable drainage systems to cope with future sea-level rise.

Evaluation: Planning creates long-term resilience but can be unpopular with developers and requires continual investment.